On the night of April 24, 1907, New York’s lamplighters left the lights out and went on strike. The 25,000 gaslights that normally kept the streets of Manhattan bright at night were never lit. As it grew darker, complaints from impatient New Yorkers to the local police poured in, but with little effect. Even by 9 p.m., the only bright public spots were a few transverse roads in Central Park, which had been equipped with electric streetlights.

Those who took up work as lamplighters that year were unlucky. Their profession was almost 500 years old, but it would soon become a distant memory. Thomas Edison’s invention of the light bulb unquestionably made the world better and brighter. But from the viewpoint of the lamplighters, who lost their livelihoods as a consequence, nothing could be more natural than resistance. Indeed, when the municipality of Verviers in Belgium announced the switch to electricity, lamplighters smashed the electric lamps in fear of losing their jobs.

The stories of the lamplighters illustrate a simple point that is also relevant to the debate surrounding the future of artificial intelligence and jobs today. Even if a new technology will benefit society at large, there will be losers in the process, and at times even outright resistance, especially if the technology threatens people’s jobs and incomes.

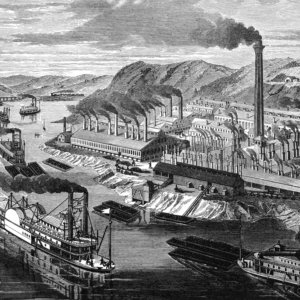

Modern growth hinges on automation. It first took off with the British industrial revolution around 1770. Before then, there were hardly any machines to relieve workers of some of their burdens. It was only with the arrival of the factory system and the introduction of machinery in production that modern economies suddenly were able to produce much more with fewer people.

Although output per worker expanded by 46% between 1770 and 1840, the gains from growth didn’t find their way into the pockets of ordinary people. Real wages were stagnant or even falling for those in the lower ranks of the income distribution, as the jobs of adult craftsmen were replaced by machines and children who were working in the factories. The living-standard crisis of the industrial revolution famously led Friedrich Engels to conclude that the machine-owning industrialists “[grew] rich on the misery of the mass of wage earners.”

Much like during the industrial revolution, today’s automation anxiety is entirely justified. Workers today are no longer reaping the gains of progress. Worse, many have already been left behind in the “backwaters of progress” (to quote the late David Landes, a leading scholar of the industrial revolution). The age of advanced robotics has meant diminishing opportunities for the middle class. Up until the 1980s, manufacturing jobs allowed ordinary working men to attain a middle-class lifestyle without attending college.

In the United States, the wages for unskilled men have fallen steadily since the manufacturing employment peak of 1979, adjusted for inflation. And since then, labor force participation among men ages 25 to 55 has fallen as well. The robots are in large part to blame. In a recent study, MIT economists Daron Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo found that each multipurpose robot has replaced about 3.3 jobs in the U.S. economy and reduced real wages.

Job automation has not happened evenly across industries and sectors. Michigan, for example, a state with long ties to the manufacturing and automotive industries has more robots than the American West. As manufacturing jobs have disappeared, social problems and dissatisfaction have risen in affected areas.

Unsurprisingly, like during the industrial revolution, the losers to technology are demanding change. My own research with Thor Berger and Chinchih Chen also shows that Donald Trump made the largest gains, relative to Mitt Romney’s presidential election result four years earlier, in communities where robots had impacted manufacturing more extensively.

While the political response has so far targeted globalization, many people now also think that holding the robot revolution back is a good idea. In a Pew Research survey conducted in 2017, 85% of the respondents in the U.S. said they are in favor of policies that would restrict robots to performing only hazardous work. Meanwhile, proposals to tax robots to slow the pace of automation have now become part of a global debate. In September, Bill de Blasio, at that time a candidate in the 2020 Democratic presidential primary, vowed to “create a permitting process for any company seeking to increase automation that would displace workers.” De Blasio has since dropped out of the race, but the threat of automation and job loss continues to play a role in debates and stump speeches of many 2020 candidates.

Continued technological progress is not inevitable. Historically, resistance to technologies that threatened workers’ skills has been the rule rather than the exception. Emperor Vespasian, who ruled Rome in 69-79, refused to use machines for transporting columns to the Capitoline Hill due to unemployment concerns. And in 1523, King Sigismund of Poland declared, “No craftsman shall think up or devise any new invention, or make use of such a thing, but rather each man shall, out of citizenly and brotherly love, follow his nearest and his neighbor, and practice his craft without harming another’s.”

Governments had good reasons to fear that automation would prompt social unrest and a challenge to the political status quo. Although much commentary tends to focus on the Luddite riots, they were just part of a long wave of riots that swept across Europe and China. Indeed, one reason why China failed to industrialize as Western Europe took off in the 19th century is the long persistence of Chinese craft guilds (gongsuo). They continued to control their craft, and they had little interest in mechanization. When a steam cotton mill company was launched in Shanghai in 1876, for example, gongsuo opposition was so fierce that local government officials refused to support the company.

As I discuss in my book, The Technology Trap, British governments were actually the first to side with innovators and pioneers of industry rather than rioting workers, which might also explain why Britain was the first country to industrialize. To be sure, Britain was once no stranger to blocking automation technologies: The Stuart monarchs did so on several occasions. Yet in 1769, the destruction of machinery was made punishable by death. Economic historians have argued that unlike in China, where the craft guilds remained a strong political force throughout the 19th century, the political clout of the guilds in Britain deteriorated as markets integrated.

Looking forward, many automation technologies loom on the horizon. Millions of people work as cashiers today, but if you shop at an Amazon Go store, you won’t see cashiers or checkout lanes. My research with Michael Osborne at the Oxford Martin School found that 47% of U.S. jobs could be automated due to recent breakthroughs in artificial intelligence. When we published our study in 2013, few analysts believed that fashion models might be automated, as we predicted. Yet, generative adversarial networks, or GANs — machine learning systems that are capable of creating fake fashion models from images — are now a reality.

Historical parallels can be overdone, but unless we are very careful, AI-enabled automation could lead to another tumultuous episode. The decades-long pause in living standards that Engel famously noted eventually came to an end in the 1840s, as new and better-paying jobs were created and workers acquired new skills. As productivity growth makes the pie larger, everyone could, in principle, be made better off. But the real challenge lies in the sphere of policy, not technology.

During the industrial revolution, the Luddites and other groups did what they could to stop the spread of labor-replacing technologies but were largely unsuccessful because they lacked an important leveraging force: political clout. Today, working people have political rights; in our current era of automation, it’s critical for technological progress to be met with good policy making.

To avoid a backlash against automation, governments must pursue policies to kick-start productivity growth while helping workers adjust to the onrushing wave of automation. Addressing the social costs of automation will require major education reforms, relocation vouchers to help people move, a reduction in barriers to switching jobs, the elimination of zoning restrictions that spur social and economic divisions, growth in the incomes of low-income households through tax credits, wage insurance for people who lose their jobs to machines, and increased investment in early childhood education to mitigate the adverse consequences for the next generation.

Learning From Automation Anxiety of the Past

No comments:

Post a Comment