Friday, October 30, 2020

Stressing customer obsession: A conversation with Sequoia Capital’s Pieter Kemps

Stressing customer obsession: A conversation with Sequoia Capital’s Pieter Kemps

Rise of the platform era: The next chapter in construction technology

Rise of the platform era: The next chapter in construction technology

Amgen’s Brian Bradbury on advancing healthcare through data analytics

Amgen’s Brian Bradbury on advancing healthcare through data analytics

Why Pronouns Speak To More Than Just Gender Differences

Earlier this year, my company, G2, launched an initiative for Pride Month called the G2 Pronoun Project. We offered a badge for anyone to download declaring what pronouns they choose to go by. In addition to sharing it across our company, we also made it available externally. For several months, I made a link to this initiative a standard part of my email signature. For me, this is a fairly big move — I take email signatures seriously and even once wrote an article about why these signatures can make important statements.

I’ve been struck by the responses we’ve received to this project and the responses I’ve personally received to my pronoun messaging. Most people have supported the idea — many of them even effusively, including people who, like me, identify by cisgender pronouns (in my case, he/him). But they’ve also seen it as a sign of something much larger than gender. They’ve viewed it as a sign of commitment to respecting everyone’s individuality.

To show respect for individuality, G2 offered downloadable templates for employees to use to assert their personal pronoun preference.

As the United States, and much of the world, reckons with racism, sexism, and other forms of intolerance in society and the workplace, what can sometimes get lost is a focus on individuality. As Paula Glover and Katie Mehnert wrote in a recent article on fixing systemic issues in organizations, “Even well-meaning people expect individuals to speak for entire groups of people. … In encouraging employees to have their own conversations with people of different backgrounds, executives and senior managers should emphasize individuality.”

This is a challenge that leaders who are committed to achieving diversity and inclusion have faced for decades. In their 1995 book Diversity in Organizations, Martin M. Chemers, Stuart Oskamp, and Mark A. Costanzo noted that diversity in organizations generally refers to “socially meaningful categorizations” but that “many people view their individuality and uniqueness as a significant part of themselves that they would not like to be overlooked.”

When it comes to identifying personal pronouns, it’s up to each individual to decide for themselves what to go by. (Even the use of “themselves” instead of “him- or herself” in the previous sentence is, to some, a sign of changing times, as Merriam-Webster has noted.) No one can look at you and tell you what pronouns you choose to use. At G2, we decided to embrace this individuality through this project, since everyone has a gender identity.

It also helps destigmatize those who may identify by less common pronouns. The LGBTQIA Resource Center at the University of California, Davis, recommends, “Make a habit of introducing yourself with your pronouns, not just in LGBTQIA-specific situations. This makes sharing pronouns routine, instead of singling out certain people or communities.”

Some business leaders may be wary of expressing openness to individually chosen pronouns out of fear of alienating people, including potential customers, who may be more socially conservative. But I’m a marketer obsessed with building relationships with as many people as possible, and I’ve found that rather than losing prospects, the practice of openly supporting people in choosing their own pronouns has built an even wider audience. And as Dipanjan Chatterjee and Nick Monroe have written, in order to appeal to younger demographics, brands need to recognize that marketing “beyond the gender binary” is critical for staying relevant in the years ahead.

Encouraging Mental Wellness

There’s also another reason why supporting individuals’ choices for pronouns is so important: Doing so can help improve mental health.

Studies have looked at the mental health of people who identify as part of a gender minority, a term the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention defines as “individuals whose gender identity (man, women, other) or expression (masculine, feminine, other) is different from their sex (male, female) assigned at birth.” People who fit into this category are more likely to experience depression, anxiety, and suicidal behavior.

Social support, in which the individual’s gender identity is accepted without stigma, can be very helpful. “Using a person’s preferred pronouns demonstrates respect and also provides a safe and inclusive environment,” New York City-based Flatiron Mental Health Counseling explains.

I’ve spoken and written about my own mental health journey, including my experiences with anxiety and depression. I’ve found that rather than stigmatizing me for it, colleagues in my company and in my broader professional community have been supportive. I want everyone to feel free to talk about their own experiences as well, and to have the same support I did.

There’s also a dollars-and-cents reason for businesses to do this. “Workplaces that promote mental health … are more likely to reduce absenteeism, increase productivity, and benefit from associated economic gains,” according to the World Health Organization.

The best workplace cultures also go a long way in attracting and retaining the best employees. At G2, one of our core values is kindness. Employees have said they see the G2 Pronoun Project as a reflection of that value.

There’s no doubt that the end of an era in which everyone had to identify as “he” or “she” will take some getting used to, and some people may remain resistant to the change. But cisgender people can help move it along by making pronoun declarations ubiquitous. That’s why I currently have mine on both my LinkedIn and Instagram accounts. I encourage leaders to put thought into how they can model similar behavior and start using personal pronouns more visibly themselves. It requires being open to new conversations, but the payoff for encouraging individuality and supporting inclusivity cannot be overestimated.

Why Pronouns Speak To More Than Just Gender Differences

The Best of This Week

Do Founder CEOs Listen to Their Leadership Teams?

To compensate for an entrepreneurial founder’s inexperience, some companies fill out their leadership teams with experienced executives. New research explores whether founder CEOs incorporate or ignore advice from their leadership teams, offering insights relevant to leaders of large and small organizations.

4 Competencies Every IT Workforce Needs

Many companies have failed at reskilling because they didn’t know the specific capabilities their employees needed to develop to fill the talent gap. This article presents research that highlights four competencies IT professionals will need in order to sustain their careers in the digital age.

Toward a More Expansive Corporate Climate Leadership

Current corporate climate leadership is largely focused on how companies can do less harm by reducing their emissions over time. But businesses can also set ambitious, expansive goals for their involvement in zoning and city planning, their support of their employees and communities, and how they might collaborate with their peers and society at large.

For Better Hiring, Identify Your Best Interviewers

Recent research provides clear evidence that some people do indeed make better interviewers than others. Using a simple methodology, you can identify your best interviewers to help decrease hiring expenses, increase the quality of new hires, and reduce employee turnover.

Teenagers Are Uniquely Vulnerable to Algorithmic Bias

Sustained, frequent exposure to algorithmic bias — systematic, inequality-perpetuating errors in predictive technologies — can shape how we see ourselves and understand how the world values us. But it can hit adolescents particularly hard, especially if they’re almost constantly online.

What Else We’re Reading This Week

- MIT SMR’s Culture 500 analysis showed the high value employees place on transparent communication by company leaders during a crisis.

- Winter is coming (to the Northern Hemisphere), along with seasonal depression. If you’re dreading the dark months, make a plan.

- “The First Day Is the Worst Day”: DHL’s Gina Chung on how AI improves over time.

- Companies should make it their business to get out the vote.

Quote of the Week:

“Resilience describes our ability to continue moving, despite whatever life throws in our path. The question for us, of course, is what causes us to be able to bounce back and keep moving, what ingredients in our lives give us this strength, and how do we access them?”

— Marcus Buckingham, New York Times bestselling author, global researcher, and head of ADP Research Institute — People + Performance, in “The Sources of Resilience”

The Best of This Week

Thursday, October 29, 2020

McKinsey for Kids: Hungry fish, baffled farmers, and what happened next

McKinsey for Kids: Hungry fish, baffled farmers, and what happened next

Responding to the demand: An interview with Vyaire Medical CEO Gaurav Agarwal

Responding to the demand: An interview with Vyaire Medical CEO Gaurav Agarwal

The coronavirus effect on global economic sentiment

The coronavirus effect on global economic sentiment

Nine scenarios for the COVID-19 economy

Nine scenarios for the COVID-19 economy

Applying machine learning in capital markets: Pricing, valuation adjustments, and market risk

Applying machine learning in capital markets: Pricing, valuation adjustments, and market risk

Optimizing water treatment with online sensing and advanced analytics

Optimizing water treatment with online sensing and advanced analytics

Remote operating centers in mining: Unlocking their full potential

Remote operating centers in mining: Unlocking their full potential

Building supportive ecosystems for Black-owned US businesses

Building supportive ecosystems for Black-owned US businesses

Do You Know Who Your Best Interviewers Are?

Organizational hiring processes vary, but one common element across companies is the vast amount of time and resources expended on interviewing — often with disappointing results. Mike, the head of a very well-funded recruitment department for a global company, described to us a particularly grueling and extensive hiring process. Every year, the company receives 300,000 applicants for just 2,000 open positions. By the final stage, a candidate will have met with and been evaluated by an average of 20 different people within the organization. An enormous amount of resources goes into the coordination and execution of this process, not to mention the indirect cost of interviewers’ time. Yet, Mike confessed, of the 2,000 new hires each year, at least half prove to be poor fits and exit the organization prematurely. He was confident that better matches existed in his candidate pool but didn’t know a more effective way to identify them.

We wanted to know whether Mike could identify the interviewers who could distinguish good matches from poor ones and persuade even the most in-demand talent to join. So we asked him a simple question: Do you know who your best interviewers are?

Mike was embarrassed to admit that he had no idea. In fact, the question had barely crossed his mind — and he’s not alone. We’ve had very similar conversations with many executives across industries.

As simple a question as it is, very few organizations have considered who their best interviewers are, and as a result, they may be leaving money on the table by failing to optimally allocate or manage their interviewers. Such inefficiencies can mean higher turnover, a lower quality of hire, and a more expensive hiring process.

Finding Top Interviewers: Evidence From a Global Contact Center

Our recent research provides clear evidence that some people do indeed make better interviewers than others and offers a simple methodology for identifying them. (See “The Research.”)

A global contact center introduced a simple tool in its applicant tracking system to monitor which employees, randomly assigned, interviewed which candidates. By tracking which candidates received job offers, accepted those offers, and turned out to be good hires — defined as those who remained with the company for at least 90 days — we linked those candidate outcomes to the interviewer who had made the hiring recommendation.

We set out to determine whether we could identify any interviewers who were doing a better job at identifying and attracting good hires than others. The data revealed the answer to be a resounding “yes”: There was significant variation in interviewer performance along each dimension we measured and, even more important, an interviewer’s performance in previous interviews was a strong predictor of his or her performance in future interviews.

In our analysis, we calculated the performance of each interviewer in his or her previous 50 interviews, controlling for seasonality, geography, local labor markets, and other factors beyond the interviewer’s control but still likely to impact outcomes. We classified those who generated a high fraction of good hires per interview the best interviewers (top third) and those who generated a low fraction of good hires the worst interviewers (bottom third).

After we classified the interviewers, we tracked their performance over their next 50 interviews and found that the past was indeed prologue: In their subsequent interviews, the best interviewers were able to generate more than twice as many good hires per interview as the worst interviewers (26% versus 12%, respectively, as described in “Time-Persistent Variation in Interviewer Performance”). This time-persistent variation is clear evidence that some people are better interviewers than others.

The difference between the best and worst interviewers is substantial in the business context. By predicting future performance based on past performance, an organization could classify interviewer performance to reassign job candidates to its best interviewers. If it were to stop using its worst interviewers altogether, replacing them with the best interviewers, the company could generate the same number of good hires with 19% fewer interviews, 8% fewer hires, and a 6% drop in six-month new-hire attrition. (See “Reallocation: Replacing the Worst Interviewers With the Best Interviewers.”)

Note also that, because the total interview workload would drop, the best interviewers would have to increase their interviewing workloads only by about 55% to take over for the worst interviewers. That reallocation amounts to significant savings in sourcing, recruiting, and turnover costs.

It’s also important to note that the best interviewers varied in their approach. Some excelled primarily because they were good at persuading candidates to join (high accept rate), others because they were good at identifying durable candidates (high stay rate), and still others because they were less likely to reject quality candidates (high offer rate). Of course, the very best excelled across all three dimensions.

Top Interviewing Practices

To better understand what various interviewer skill sets look like in practice and how these differences can present themselves in real business contexts, we offer three suggestions gleaned from our qualitative research.

Balance individual interviewers’ approaches with a multistep interview process. Benjamin was the CEO of an expanding global technology company who frequently interviewed prospective leadership hires. His interviewing style was less focused on evaluating the candidate than on offering a vivid sales pitch to excite candidates about the prospect of joining his company. After an hour-long interview of this style, however, Benjamin might not have learned a thing about the candidate or whether his or her skill set, background, and personality fit the organization’s needs. In short, this CEO is the last person you should ask about whether a candidate should be hired.

There’s nothing necessarily wrong with this approach. Leadership hires typically go through several rounds of interviews and screening, and it may not be every interviewer’s job to assess candidate fit. This CEO’s passion made him highly effective at attracting top talent and persuading people to join his organization, relying on his colleagues to handle the screening.

Multistep interview processes allow for, and can benefit from, a certain degree of specialization. What’s important is that hiring teams are aware of these interviewer skill differentiations and get clear about who’s good at what.

Practice transparency. Sky-high employee attrition at a U.S. call center meant its hiring team was continuously fighting to meet ambitious quotas in a tight labor market. Much of the team was determined to make the job seem attractive so that applicants would agree to show up for onboarding and training. Unfortunately, many new hires quit after just a few weeks on the job, realizing it wasn’t a good fit for them — and leaving yet another vacancy to fill.

Recognizing this vicious cycle, hiring manager Sarah used the interview process to present an honest, realistic assessment of what the job was like, rather than portraying it as universally appealing. She intentionally highlighted the divisive aspects that employees felt strongly about, such as off-hour shifts, and she translated the company’s heavily performance-based compensation plan into realistic wage estimates (“around $10 to $15 an hour”) rather than attractive but largely unattainable estimates (“up to $50 an hour!”). By providing an accurate description of the job, she allowed candidates to assess for themselves whether they would really be happy working there.

After Sarah adopted this strategy, the candidates she interviewed were a bit less likely to accept job offers — but those who did were a much better fit. Sarah emerged as the top interviewer on her team: The 90-day quit rate of her candidates was by far the lowest, and she generated the highest fraction of good hires per interview. By recasting the interview as an honest exchange of information and giving the candidate an opportunity to realistically assess the job opportunity, Sarah was able to weed out bad-fit candidates before the company invested thousands of dollars in onboarding and training them. When leadership saw her success, they asked her to run a series of workshops explaining her interviewing approach across the company.

Rethink deal breakers. A global business process outsourcing company also struggled with high employee turnover and perpetual vacancy rates, so its chief goal was to find as many qualified, reliable new hires as possible.

With lots of interviewing experience, Robert had pinpointed a few deal breakers — behavioral signals, such as requesting to reschedule an interview at the last minute — that indicated to him that a candidate wouldn’t succeed if hired. He used these signals to eliminate otherwise qualified candidates from consideration. In contrast, Robert’s colleague and fellow interviewer Alice saw potential where Robert saw liability, and she eliminated far fewer candidates on the basis of her guesses about their future behavior.

Even though Robert was much more stringent, the average quality of his hires was no better than Alice’s — but because of Robert’s deal-breaker rejections, he was missing out on valuable talent. When he saw that Alice was bringing in good hires in far greater numbers, he reevaluated his deal breakers and started extending more offers.

Practical Implications and Extensions

The data clearly shows that some interviewers are better than others, that different interviewers take different approaches, and that interviewers can excel on distinct metrics like offer, accept, and stay rates. But if organizations don’t know who their best interviewers are, or in which area each interviewer excels, they’re unlikely to utilize or manage that talent effectively.

Identifying your company’s best interviewers is simple: Decide on the candidate outcomes that matter, and evaluate interviewers on the basis of how their interviewed candidates perform on those outcomes, controlling for extraneous factors like seasonality or local labor markets. The definition of a good hire can vary by organization and may include metrics like employee performance ratings, productivity metrics, manager assessments, or employee retention. While an interviewer’s average past performance will be a reliable indicator of his or her future performance, keep in mind that reliability will increase as the interviewer conducts more interviews. (The metric should be highly reliable by the time the interviewer has conducted 25 to 50 interviews, but our data shows that outcomes from as few as five interviews can consistently predict future interviewer performance.)

This methodology allows for tremendous flexibility. The metrics used to evaluate performance can be tailored to each organization’s specific goals. For those concerned with diversity in their hiring practices, measures like offer rates to women and racial or ethnic minorities could be included. For hiring teams that use candidate experience survey tools, employer brand metrics like Net Promoter Score might be an important component of interviewer performance.

Companies can leverage this information about interviewer performance in several different ways. They can try to reallocate interviews to their top interviewers or allocate interviews based on specific interviewer strengths — for example, by sending female candidates to interviewers who excel on diversity metrics, or sending candidates with competing offers to the interviewer with the best “sales” record of accepted offers. Sharing performance information strategically can encourage interviewers to improve their numbers. Companies can design incentives to reward their best interviewers or use interviewing outcomes as input for performance ratings.

Interviewers can use this information to learn about their specific strengths and weaknesses. Top interviewers can share successful interviewing strategies with their colleagues, enabling peers to learn and adopt approaches that work well. Improving interviewer ability is particularly important for smaller organizations that may not have much flexibility in who conducts interviews.

You can’t manage what you don’t measure. By bringing visibility to the interviewing process, organizations can achieve significant improvements in their hiring process and realize substantial value. The next time we ask an executive whether they know who their best interviewers are, we hope the answer is yes.

Do You Know Who Your Best Interviewers Are?

Wednesday, October 28, 2020

The Four Competencies Every IT Workforce Needs

Image courtesy of Daniel Hertzberg/theispot.com

The digital revolution is forcing the rapid transformation of IT departments and compelling them to do more than take care of infrastructure and basic services. Today’s IT organizations must be strategic partners with business leaders to help them execute digital strategies and capitalize on emerging technologies in order to generate entrepreneurial opportunities and disruptive ideas.

Despite their pivotal importance to digital transformation, many IT departments are simply not prepared for these new demands. According to a recent World Economic Forum report, IT skill shortages and training requirements are the key factors slowing down digital transformation.1 The talent gap in the IT workforce is not about a lack of specific technology skills; rather, it’s about being able to solve business problems and create new opportunities for technology-enabled businesses.

Many companies have failed at reskilling — the process of preparing people for new jobs and new roles — because they didn’t know the specific capabilities their employees needed to develop to fill the talent gap.2

We set out to understand what competencies are essential for IT professionals in the digital age, by interviewing senior technology leaders from a cross section of industries and studying a global telecommunications company based in Europe. (See “The Research.”) The research revealed that digital business demands four behavioral competencies — qualities that transcend technical proficiency to embrace interpersonal skills and a drive for continuous learning — that enable IT talent to meet current and future business needs.

1. Learn to manage role complexity. As IT departments are increasingly looked at as equal business partners and strategic enablers, the IT workforce also needs to be able to take on a more direct value-creation role, such as participating in decision-making that affects the customer experience. This means that a company’s ability to deliver digital products and services that are differentiated from those of competitors requires more in-house software development expertise than in the past. There is less demand for traditional capabilities, like the ability to coordinate outsourced work, and a greater need for creative engineers, software developers, and advanced data analysts.

IT roles are also becoming more complex because they now require individuals who can collaborate with colleagues who have different specializations than they do. Our research suggests that companies are increasingly deploying teams whose members have experience in a variety of functional areas. Companies also have team members with “T-shaped” skill profiles — that is, people who have expertise in one area as well as enough additional knowledge to collaborate with experts in other areas so they can perform complex and adaptive IT functions together.

For example, scrum, the popular methodology for Agile software development, requires the individual members of developer teams to be able to perform all of the tasks needed in the software development process: business analysis, architecture, design, development, testing, deployment, and operations. Previously, each task was assigned to a single person or group, often from different departments. Similarly, the increasing use of T-shaped skill profiles in software development teams means that both the depth and the breadth of individual skills are expanding: Each team member is expected to be an expert in one domain or task — such as coding or software development — but is also expected to develop complementary skills by working with experts in other domains or tasks, such as software operations and maintenance.

In the telecom company we studied, individuals working in teams with end-to-end responsibility for a product recognized that their roles were more complex, but they perceived that the benefits outweighed the costs. Receiving direct customer feedback on the products or services they developed not only improved IT workers’ understanding of customer demands but also helped them feel that their work was important for the company’s success and improved their confidence in decision-making.

Indeed, our employee survey found that, on average, IT workers feel more comfortable in managing increased role complexity when they can see how their responsibilities and actions directly impact business outcomes. The survey respondents who saw a clear link between business outcomes and their own responsibilities and actions perceived that they were better able to manage complex roles than their peers who did not see a clear link between business outcomes and their responsibilities and actions.

Leaders must make it clear that these changing roles and ways of working present opportunities for IT workers to create value for their companies, in addition to increasing the value of their skills and improving their own career paths.

2. Connect, collaborate, and integrate knowledge swiftly. As companies advance in their digital transformations, their IT

infrastructures have to become more open and flexible so they can explore and exploit a wide range of emerging opportunities to create value and achieve faster time to market.

This requirement to take advantage of new tools, technologies, engineering approaches, and entrepreneurial insights places a premium on IT workers who can connect and cooperate with experts from a variety of disciplines and domains. In our research, technology leaders highlighted the need for employees to swiftly integrate new knowledge and problem-solving strategies into their current work.

These trends also influence the way companies set up their IT organizations. We found that the companies most affected by digital disruption are increasingly replacing the traditional model of hierarchical management with a more Agile collaboration model, with teams empowered to make and execute decisions.

Technology leaders in our study said that self-empowered teams usually develop, test, and launch solutions more quickly than teams in hierarchical organizations.

As a senior vice president of IT at the telecommunications company told us, “By reducing hierarchical layers of decision-making, we foster speed and directly integrate decisions into practice. These high-performance teams also benefit from the trust of their leaders in their competencies.”

Shifting decision-making to the “experts” — that is, the IT workers — is empowering on several levels, says Mattias Ulbrich, CIO at Porsche: “People who have the absolute responsibility for what they are developing tend to develop better products and come up with more creative solutions and concepts that are thought through more thoroughly. The manager-developer relationship changes from ‘Do this’ to ‘How can I help you?’ which creates more trust and quality work. In this way, trust becomes the biggest time and money savings factor and the most important requirement for good relations.”

In our survey, the findings suggest that IT employees feel able to work across organizational boundaries when their bosses delegate more strategic decisions to them and provide them with resources, such as budgets for client visits. They also find it helpful when the company assigns them a partner or mentor from other teams or divisions, such as through job shadowing, and when leaders from different functions and business lines in the enterprise act as role models for crossing organizational and team boundaries.

3. Embrace and manage contradictory demands. The digital age requires IT organizations to manage conflicting demands. First, they have to excel in their traditional role of providing infrastructure, high-quality service, and security, all with rising performance and at a lower cost. At the same time, they have to be business enablers and help their companies sense and seize opportunities made possible by emerging technologies. This requires a shift from being an organization that reacts to demands to one that is proactive.

Achieving this shift requires that IT organizations deliver an ambidextrous response: one that can exploit existing IT capabilities for operational efficiency and excellence while simultaneously identifying new IT capabilities to help innovate and create differentiated customer value.

According to our study, some companies enable ambidexterity at the individual level. Employees working in the two modes described above set goals together, planning and prioritizing features at the beginning of a product release cycle or sprint. They analyze and identify the potential conflicts between the old and new IT structures in terms of budgets, priorities, and responsibilities. To succeed, IT workers must be proficient in both modes of working.

Ambidextrous employees are those able to embrace the tension between IT’s traditional capabilities and the new ones required by the digital age. Those who maintain traditional operations learn to understand innovation and serve as enablers for new solutions from those who are working in innovation or exploration mode. Instead of seeing inconsistencies as a threat, they view them as a source of creative conflict that can be built upon to create value. This requires those employees to learn to live with dual agendas and conflicting time horizons.

Our survey findings suggest that IT workers can cultivate their own ambidextrous experiences when their leaders demonstrate an appreciation for behaviors such as exploring new approaches, taking risks, and dealing well with failure. We found that IT employees working with leaders who encourage risk-taking without instilling the fear of failure reported, on average, a 30% greater score for novel and innovative activities and approaches compared with peers working with leaders who leave little room for experimentation and exploration. Several senior technology leaders reported that it’s also helpful when leaders cultivate a culture of experimentation in which they share their own failure stories.

Companies can also foster an innovative mindset by providing development platforms for testing and trying out new ideas and solutions. The telecom company we studied is using a development sandbox isolated from the company’s production chain, where employees can explore new product and service ideas and solutions.

The company also organizes events such as hackathons — days where IT employees assemble to develop a prescribed business or design idea within a given time frame — and innovation sprints, in which IT employees create something novel outside of their normal work routines. These company-sponsored

exercises foster both creativity and collaboration.

4. Master continuous learning and adaptation. The digital age has increased the pace of change in both business and technology. At the same time, it has become more difficult to predict what specific skills will be needed, even in the very near future. This makes ongoing education, both on the job and outside of it, critical for IT workers and their companies.

Our research findings indicate that both IT employees and their employers understand that workers need to be able to learn from their own experiences — and those of others — on a continual basis to become better at their current jobs and better prepared for future roles. Employers need to provide learning opportunities, and IT workers must have the drive to absorb lessons, acquire new skills, and gain insights from feedback.

Some companies facilitate this continuous personal growth by embedding learning opportunities in the design of regular work processes. For example, some teams working in scrum are employing the framework’s “inspect and adapt” principle and can learn from their experiences and mistakes in targeted feedback loops. This is not limited to task feedback but also includes feedback about the skills, behavior, and performance of the individual team members. At every step of the way, through the changes and improvements to products and processes, teams must focus on the overarching business goal and the activities that best solve a given business problem.

Our research found that learning opportunities are more effective when the IT workforce has some leeway in managing individual learning and progress. Our survey findings suggest that employees feel more motivated and empowered when leaders facilitate development by providing proactive coaching and feedback, support on functional and methodological issues, and communications platforms (virtual or otherwise) for the purposes of open debate and discussion.

Employees perceive it as a major demotivator, however, when leaders unilaterally define and prioritize learning targets without involving them in the goal-setting process. Those who have a stronger influence on their learning targets tend to exhibit greater motivation for exploratory activities. Furthermore, most respondents did not perceive financial prizes such as extra pay as effective motivators for achieving developmental goals.

The findings make sense to IT executives like Porsche’s Ulbrich. “The core value of letting people pursue their very personal learning experiences is intrinsically motivating. Especially young talents, who bring in new perspectives and creativity, are not motivated by rigid cultures, which they perceive as very limiting. Leaders who lead through enabling instead of dictating can be role models who support a positive culture of learning and competency development,” he says.

A Career That Transcends Technical Skills

The four behavioral competencies described here are capabilities that IT employees can and must learn in order to perform well in their new and redefined roles for their companies as they adapt to the requirements of digital business. They provide the chance for IT professionals to continuously update their technical skills for specific tasks while building interpersonal skills and developing a habit of lifelong learning that will help them build lasting careers in a dynamic field.

For corporate leaders, ensuring that your IT workforce is future-proofed for the digital age makes it imperative that new talent strategies prioritize these four behavioral competencies in hiring, training and development, and promotion — because in the digital age, technical skills alone are not enough.

The Four Competencies Every IT Workforce Needs

Reimagining how life sciences work will be done in the next normal

Reimagining how life sciences work will be done in the next normal

Executive’s guide to developing AI at scale

Executive’s guide to developing AI at scale

Software and the next normal: A talk with Workday’s cofounder and co-CEO

Software and the next normal: A talk with Workday’s cofounder and co-CEO

The impact of COVID-19 on the global petrochemical industry

The impact of COVID-19 on the global petrochemical industry

The path to true transformation

The path to true transformation

How Companies Are Winning on Culture During COVID-19

At first glance, you might expect COVID-19 to be a disaster for corporate culture. The widespread shift to remote work — half of employees in the U.S. were working from home in April — decreased the face-to-face interactions that reinforce organizational culture.1 The economic downturn in many industries and a spike in layoffs threaten to unravel the social fabric that holds companies together.

Our ongoing analysis of 1.4 million employee-written reviews on Glassdoor, however, tells a very different story. To examine how the pandemic has influenced employees’ perceptions of corporate culture, we looked month by month at how workers at Culture 500 companies rated their employer for the five years through August 2020. When current or former employees review a company, they are asked to rate its culture and values on a five-point scale, from “very dissatisfied” to “very satisfied.”

We found that the average culture rating across the Culture 500 companies experienced a sharp jump between March and April 2020. (See “Company Culture and Values Ratings Before and During COVID-19.”) The months of April through August 2020, which saw widespread lockdowns, shifts to remote work, and layoffs, occupy the top five spots in terms of average culture ratings during the five-year period.

To understand what was driving this positive spike in culture ratings in the COVID-19 era, we analyzed how employees discussed more than 200 topics in company reviews during the 12 months before the coronavirus pandemic. Our natural language processing platform identified which topics employees mentioned in the free text of their Glassdoor reviews and whether they talked about them positively or negatively. We then compared how often and how favorably those topics were discussed pre-COVID-19 with results from reviews written during the pandemic.2

For most topics, there was little difference in sentiment before and during the coronavirus pandemic.3 But one important theme that does stand out in the months of the pandemic is the quality of communication by leaders. Employees of Culture 500 companies gave their corporate leaders much higher marks in terms of honest communication and transparency during the first six months of the coronavirus pandemic compared with the preceding year.

Employees were twice as likely to discuss the quality of communication by top leaders in positive terms during the months of the pandemic than they were a year earlier. In fact, they were 88% more likely to write positively about leaders’ honesty and transparency (46%). Employees also expressed more positive sentiment about transparency (42%) and communication (35%) in general. (See “Employees Gave Companies High Marks for Communication and Integrity During COVID-19.”) Companies on our Culture Champions list, including HubSpot, Hilton, Ultimate Software, Nordstrom, and HP Inc., scored particularly well on transparent communication during COVID-19.

The theme of transparent communication is relatively rare among official corporate values. In an earlier study of the corporate value statements of more than 500 larger companies, we found that only 12% listed transparency or communication among their official corporate values. Because it is relatively rare in corporate culture statements, transparent communication is not included among our Big 9 values measured in the Culture 500.4 During times of crisis, however, the quality of communication is central to how employees evaluate corporate culture.

This importance of communication and transparency in the Glassdoor data is consistent with findings from other studies. In late April 2020, we asked over 400 HR leaders an open-ended question about the most meaningful thing their organization did to support the transition to remote work during COVID-19.5 High-quality communication was the top answer, mentioned by nearly half of all respondents. A separate survey found that employers were the most trusted source of information on the coronavirus, ahead of government officials, traditional news outlets, or social media.6

In their Glassdoor reviews, employees spoke highly about the level of integrity that their leaders, and their company as a whole, displayed in dealing with the COVID-19 crisis. Employees were 57% more likely to talk positively about ethical behavior during the pandemic and 51% more positively about the company’s compliance with regulations. Integrity is the most common official corporate value, listed by 65% of companies we studied, and is included among the Big 9 values. Culture 500 companies also received positive reviews regarding leaders treating employees fairly and embodying corporate values in the midst of the pandemic.

Financial services companies, including The Hartford, U.S. Bank, and TIAA, were among the leaders in integrity during COVID-19, along with SAP, Marriott International, and Lockheed Martin.

Of course, not everything was good news. Culture 500 employees spoke more negatively about their company’s lack of agility during the first six months of COVID-19 than they did in the preceding year. Employees spoke more negatively about the level of bureaucracy, the complexity of processes, the speed in responding to changes, and a lack of entrepreneurship. (See “Employees Give Companies Low Marks for Agility During COVID-19.”) While employees, on average, believed that their leaders responded ethically and communicated well during the crisis, they were less positive about their employer's flexibility in responding to the global pandemic as well as to the recession, economic uncertainty, political unrest, and widespread protests.

We also analyzed which topics employees were more likely to mention during the first six months of COVID-19 compared with the preceding year. For most topics, there was little difference in terms of how frequently they were discussed before and during the coronavirus pandemic.7 But a few important themes do emerge. Not surprisingly, employees were two and a half times more likely to mention the word recession after March 2020 compared with the preceding year. (See “Which Topics Employees Were More Likely to Discuss During COVID-19.”) Other themes that employees talked about more frequently include mental and physical well-being; transparent communication by leaders; and diversity, equity, and inclusivity.

Comparing the Extremes

To gain insight into what the best companies did differently during the first six months of the pandemic, we first calculated the difference in a company’s average score across culture values before and during COVID-19. The typical company experienced a small increase in its culture values score, but a few companies saw their scores rise significantly.8 We created a subset of the 50 companies in our sample that experienced the biggest gain in their culture values score (the top 50) and compared them with the 50 companies that experienced the largest decline on that measure (the bottom 50).9

We then identified the topics that experienced the biggest bumps in sentiment scores (positive or negative) during COVID-19 in the top 50 companies and the biggest decreases in sentiment among the bottom 50 companies. (See “Culture During COVID-19: Companies With the Biggest Gains Excelled at Communication, Employee Welfare, and Agility.”) In the top 50 companies, for example, employees talked about transparent leaders 43% more positively during the early months of the pandemic compared with the preceding year, while employees in the bottom 50 companies discussed that topic 17% more negatively during COVID-19.

Communication again emerges as the most important differentiator between companies that saw a significant boost in their culture values score and those that suffered a sharp decline. The top 50 companies excelled at transparent leadership, effective top team (senior leadership) communication, and clearly communicating strategy throughout the organization, and they fared well in employees’ general assessment of transparency throughout the company.

The top 50 companies also did a much better job in addressing issues related to employee welfare. They put in place policies that helped employees balance work with family responsibilities, protected employees’ physical health and safety, and supported their mental well-being. Companies like Deloitte, IBM, and SAP scored particularly well on these dimensions.

The top 50 companies also responded to environmental changes with more agility. Employees in the leading companies were more positive about their employer’s focus on the external environment, experimentation with new ways of working, flexibility of processes, and ability to execute strategy despite market changes.

A recent New York Times article argued that business leaders failed to live up to their responsibilities as corporate citizens during the early months of the coronavirus pandemic. Our analysis of more than 330,000 employee reviews on Glassdoor, however, finds that employees of large companies gave their leaders a strong vote of confidence in responding to COVID-19 — the five highest-scoring months in terms of culture and values were April through August of 2020. Corporate leaders in the companies we studied have, on average, received high marks for transparent communication and integrity. The very best companies further distinguished themselves by supporting their employees’ well-being and exhibiting agility in response to unprecedented circumstances.

How Companies Are Winning on Culture During COVID-19

Tuesday, October 27, 2020

Data: The next wave in forestry productivity

Data: The next wave in forestry productivity

The three building blocks of successful customer-experience transformations

The three building blocks of successful customer-experience transformations

Consumer sentiment and behavior continue to reflect the uncertainty of the COVID-19 crisis

Consumer sentiment and behavior continue to reflect the uncertainty of the COVID-19 crisis

Digital Challengers in the next normal – Romania in the CEE context

Digital Challengers in the next normal – Romania in the CEE context

Reimagining the auto industry’s future: It’s now or never

Reimagining the auto industry’s future: It’s now or never

Mastering complexity with the consumer-first product portfolio

Mastering complexity with the consumer-first product portfolio

Why most eTrucks will choose overnight charging

Why most eTrucks will choose overnight charging

Monday, October 26, 2020

Insurance strategy in Asia: Using programmatic M&A during the pandemic

Insurance strategy in Asia: Using programmatic M&A during the pandemic

Reimagining higher education in the United States

Reimagining higher education in the United States

A fast-track risk-management transformation to counter the COVID-19 crisis

A fast-track risk-management transformation to counter the COVID-19 crisis

Reimagine Your Next Chapter With Resources From MIT SMR

The scale and variety of disruption we’re experiencing this year are astounding. In the face of economic, public health, and political crises, leaders have scrambled this year to manage uncertainty and keep their organizations productive and moving forward.

It’s a time of challenges, but it’s also an opportunity to rethink what’s next, develop new strategies, and execute in new ways.

We can help you think through the tough issues and get you focused on your company’s next chapter. I invite you to spend some time on the MIT SMR site, where all of our articles, reports, videos, and interactive tools are freely available to everyone through Thursday.

To get you started on this free reading spree, we’re offering some recommendations here. Among them is a special report from our fall 2020 magazine that shines a spotlight on how to reboot your strategy in the wake of COVID-19. We’ve also published thoughtful essays from diverse experts on how work has changed and will continue to change even more in a remote work landscape. New releases from the Culture 500 project will provide you with insights into what matters most to employees today and can help you seize the opportunity to build a culture that will sustain you through uncertainty.

I hope the selections below are helpful to you. We’d love your feedback.

Reimagine Your Next Chapter With Resources From MIT SMR

The Sources of Resilience

We’re all suffering through difficult times that we did not anticipate and challenges that we were not prepared for. In the face of all that’s going on in the world, how do we survive? How do we push through the muck of current events and continue showing up for the people who need us most?

The answer to many of these questions lies in our capacity for resilience: the ability to bend in the face of a challenge and then bounce back. It is a reactive human condition that enables you to keep moving through life. Many of us live under the assumption that a healthy life is one in which we’re successfully balancing work, parenting, chores, hobbies, and relationships. But balance is a poor metaphor for health. Life is about motion. Life is movement. Everything healthy in nature is in motion. Thus, resilience describes our ability to continue moving, despite whatever life throws in our path. The question for us, of course, is what causes us to be able to bounce back and keep moving, what ingredients in our lives give us this strength, and how do we access them?

Some aspects of resilience are trait-based; that is, some people will naturally have more resilience than others. (You only need to have two children to know the truth of this.) In this sense, resilience is like happiness: It appears that each of us has our own set point. If you have a high happiness set point, your happiness may wane and dip on bad days, but you will generally be happier than someone with a lower set point. Similarly, each person has his or her own resilience set point. If yours is relatively low, you will have a harder time bouncing back from challenges than, say, Aron Ralston, who got trapped while hiking in Utah and famously amputated his own arm to free himself.

How can you create for yourself — and for those you love and lead — a greater capacity for resilience, regardless of your initial set point? To answer this question, my team at the ADP Research Institute conducted three separate studies.

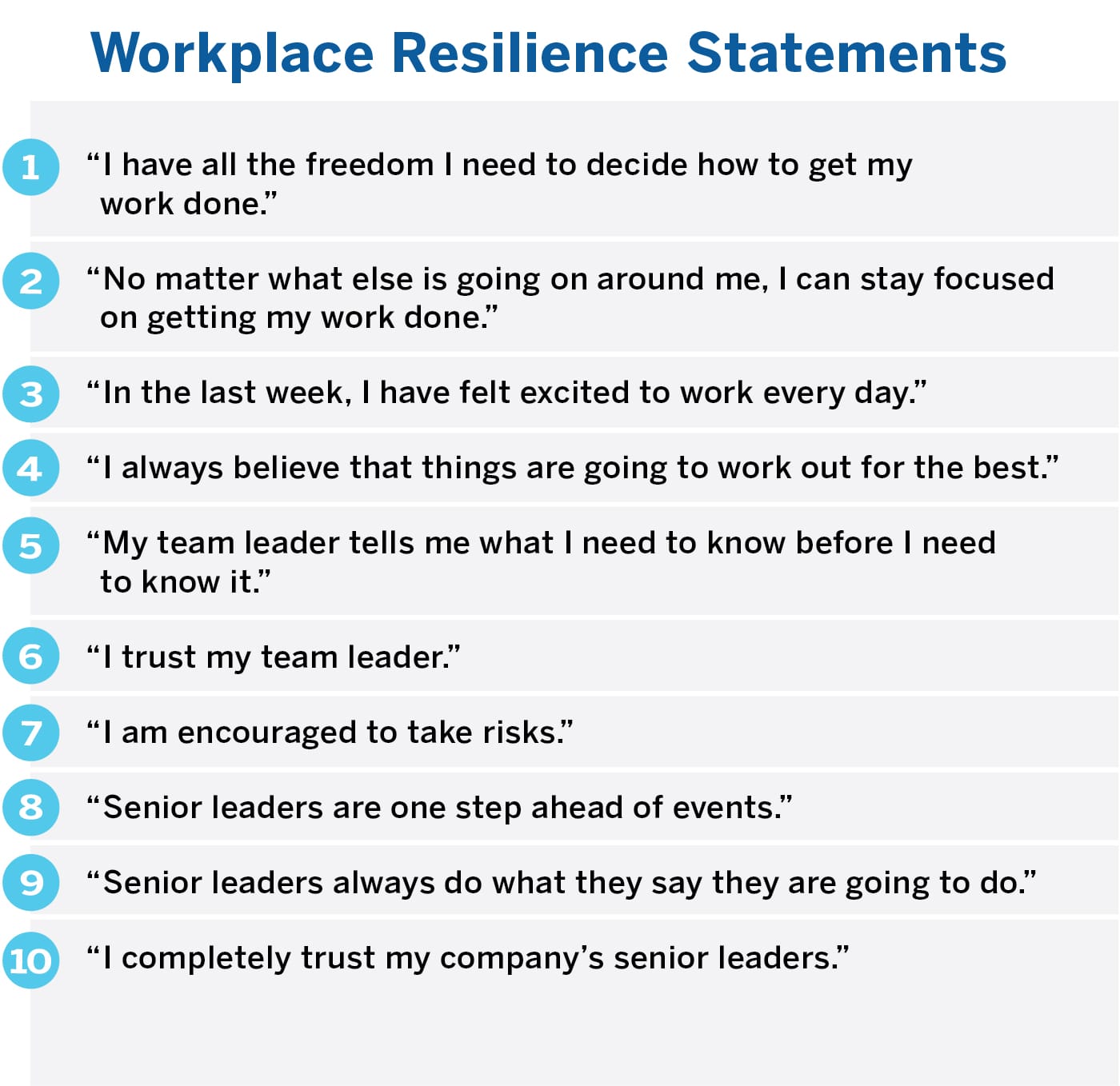

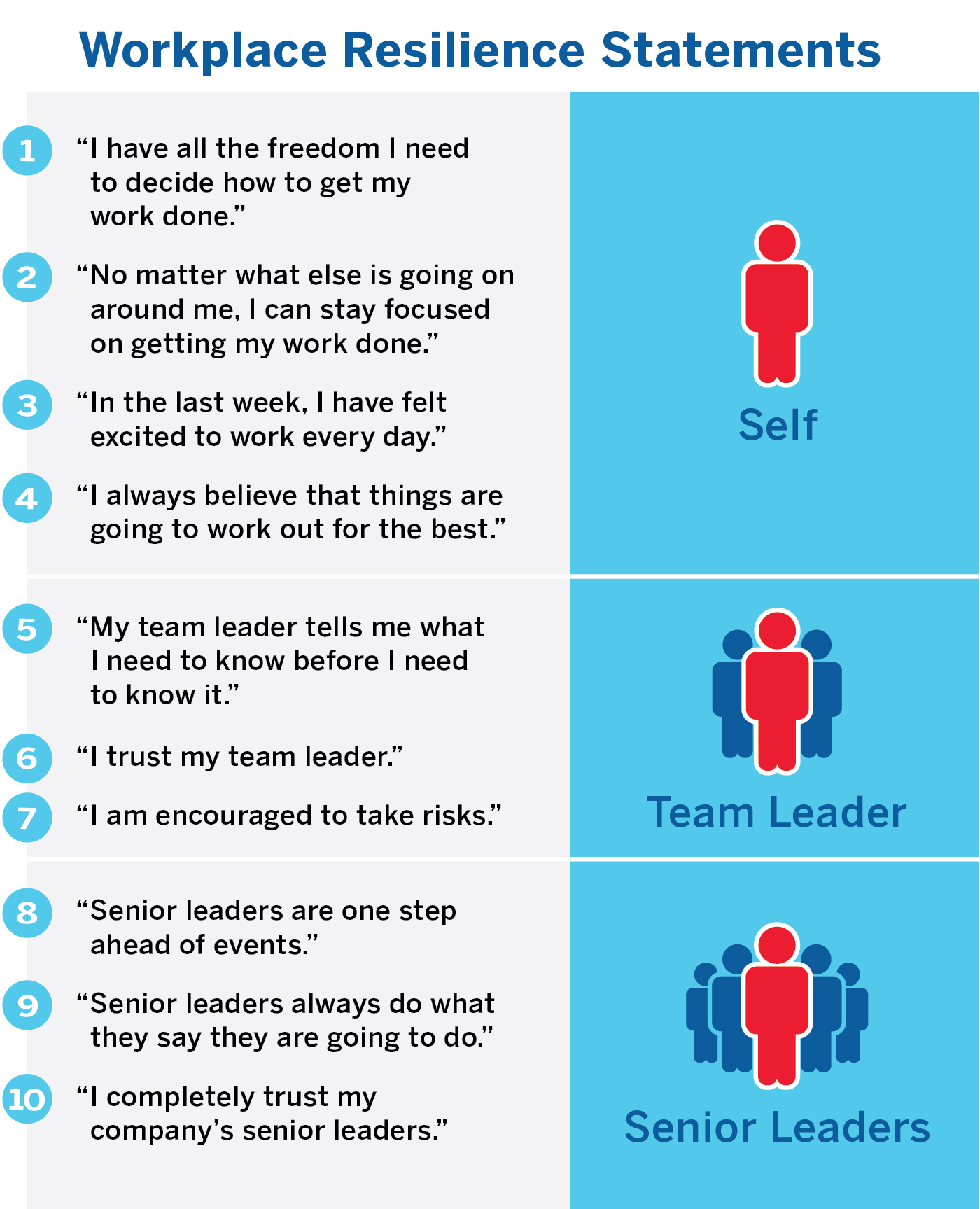

The first study experimented with many different sets of statements and asked respondents to rate how strongly they agreed or disagreed with each one. This helped us determine which statements had the strongest relationship to resilience-like outcomes such as increased engagement, reduced voluntary turnover, and fewer accidents on the job. From this study, we identified 10 statements that proved to be the most reliable for measuring resilience.

Second, we did a confirmatory analysis with a different sample of respondents to understand how these questions worked together and to validate the model we created from the first survey. Finally, we deployed our survey instrument to 26,000 people around the world to understand both the different levels and patterns of resilience in different countries. You can find the full results from the Workplace Resilience Study on the ADP Research Institute’s website.

In this article, we share the 10 most powerful resilience statements, what these questions reveal about the sources of resilience, and what can be done to create more of it.

The 10 Resilience Statements

Ten statements survived this rigorous analysis. Of course, we’re not suggesting that these are the only statements that measure resilience. But we do know that these statements, worded in precisely this way, prove reliable in measuring thoughts and feelings associated with resilience, and that as a group they demonstrate acceptable levels of content and construct validity. More research will need to be undertaken to establish their predictive validity.

Right off the bat, it’s clear that these statements all share two characteristics. First, each one contains only a single thought; survey statements containing multiple thoughts confuse respondents and generate “noisy” data. Second, these statements ask respondents to rate only their own feelings and experiences rather than somebody else’s attributes or qualities. This is because we humans are hopelessly unreliable raters of other people, capable of reporting only on our own subjective experiences.

At a deeper level, though, these statements pinpoint three sources of resilience. Statements 1 through 4 address employees’ own actions and mindsets, statements 5 through 7 address the actions of their team leader, and statements 8 through 10 address the actions of their organization’s senior leaders. It is this ecosystem of your own feelings, combined with how your team leader and your senior leaders behave, that creates your overall sense of resilience.

The statements also lead us to specific prescriptions for what senior leaders, team leaders, and individuals can do to increase their own and their organization’s levels of resilience, which we’ll explore from senior leadership down to individual contributors.

Senior Leaders

If you are a senior leader looking to build resilience in your teams (and teams of teams) within your organization, you’ll want to focus on two things: vivid foresight, as in statement 8, and visible follow-through, as in statements 9 and 10.

Vivid foresight. We — your employees — don’t expect senior leaders to predict the future, but we do need you to show us that you’re able to look around the corner and see a few things that you’re certain of. Situations and circumstances change, yet some things we can be sure of nonetheless. So, please, dear senior leaders, rally us around those certainties. Tell us who we will still be serving once we round that corner. Remind us what our competitive advantages will be in the near-term future. Reanchor the values that will hold true no matter what. The more vividly you can rally these certainties — in the form of stories you tell us, or heroes you point to, or examples from your own life — the more resilient we will be.

Visible follow-through. We don’t need grand pronouncements from you. We’re aware that during extraordinary times such as these, you can’t possibly know whether you’ll be able to deliver on these grand promises. Instead, find a few things you can absolutely commit to doing — what the organization will do for its customers in the near term, or what new piece of tech will be provided for a particular group of employees — and do them. Then shine a spotlight on them and show us how your commitments led to action. These small commitments may relate to only a small subset of employees rather than all employees, but it doesn’t matter who’s on the receiving end of these commitments of yours. What does matter is that we see you frequently making small commitments and then delivering on them. Do this again and again, and over time our trust in you will grow, and so will our sense of resilience — a little every day and a lot over time.

Team Leader

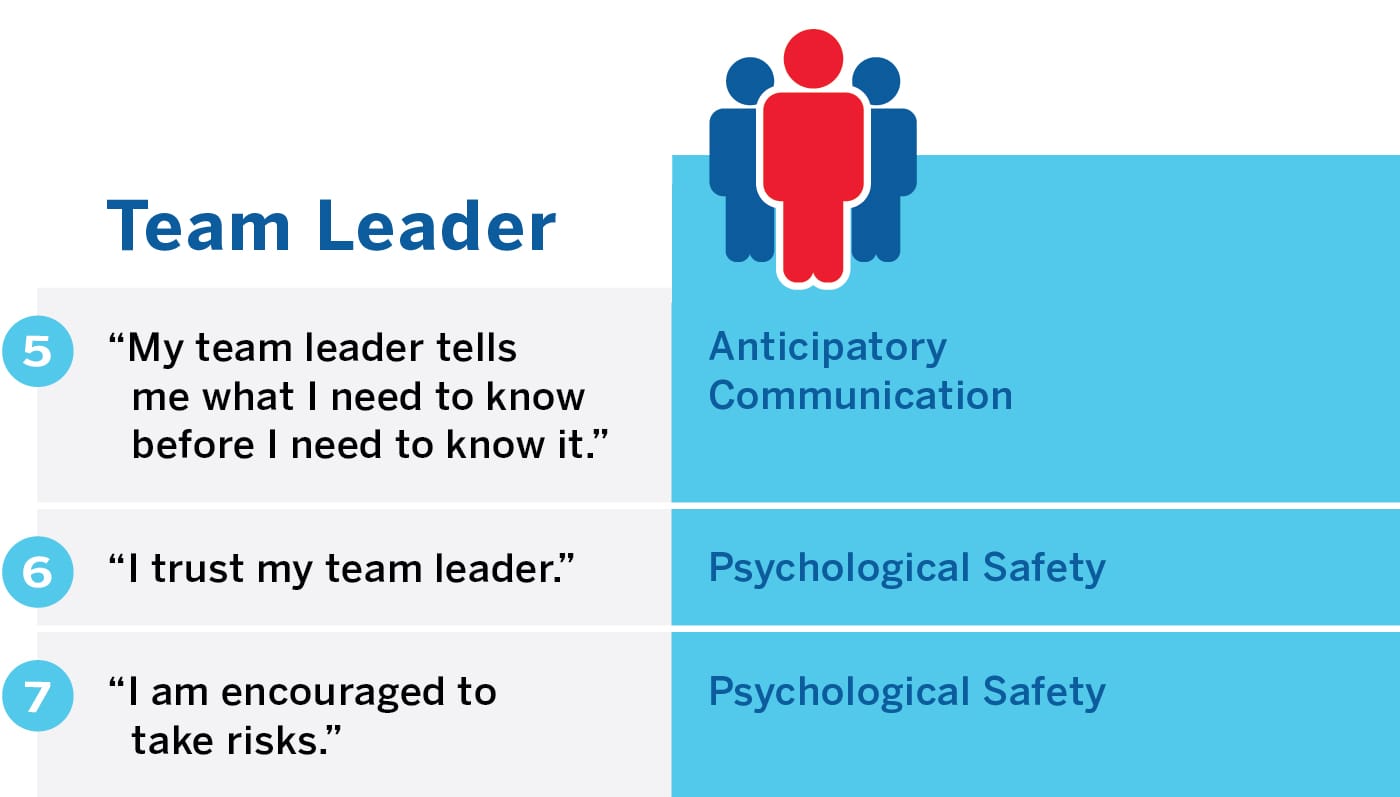

As a team leader, what exactly can you do to build resilience on your team? The three specifics we found can be distilled into two needs: anticipatory communication (statement 5) and psychological safety (statements 6 and 7).

Anticipatory communication. A significant body of research reveals that the single most powerful ritual shared by the most effective team leaders is a short weekly check-in with each person on the team. This check-in is a one-on-one conversation during which the team leader asks two simple questions: “What are your priorities this coming week?” and “How can I help?” No matter what their industry or level, those teams whose leaders discipline themselves to stick to this weekly check-in routine display significantly higher levels of performance and engagement and lower levels of voluntary turnover.

These weekly check-ins help each team member stay focused on the right priorities, which clearly drives engagement, but they also are an excellent way for a team leader to build resilience in the team. In each brief check-in, the conversation will naturally surface some details about the week to come. The two of you, while discussing priorities, can identify plans or processes that might need to change, gather the resources needed to get work done, and anticipate challenges that impact plans. In so doing, you will inevitably find yourself sharing things that the team member needs to know — before they even know they need to know it. And thus their resilience will grow.

Frequency of short interactions is the best response to times of dynamic change. These frequent interactions ensure that the two of you — team leader and team member — are engaging with, talking about, and making decisions in response to the real world as it actually is now, no matter how quickly it might be changing.

Psychological safety. At the start of this research, a link between risk and resilience was by no means inevitable or expected. But in statement 7, “I am encouraged to take risks,” you’ll see that one’s willingness to accept and even encourage risk-taking is a significant factor in how resilient one can feel. During difficult times, we all have to come up with new ways of getting work done. With a team leader who gives us the freedom to try new methods of collaborating, of working, of making things happen — when we feel that psychological safety — we feel more resilient.

To grow resilience on your team, be sure to emphasize that you fully expect team members to come up with new ways of doing things. Underscore that although some of these approaches will be more successful than others, you will always support people’s efforts to innovate and reinvent.

Self

Lastly, what can you do to ensure that you, yourself, are as resilient as possible?

Agency. Statement 1, “I have all the freedom I need to decide how to get my work done,” includes a clear sentiment of agency. This pandemic has emphasized that we are more responsible than ever for making our own choices. We are all tasked with figuring out how to get work done amid this stress and strain — not to mention the many distracting implications of working from home. But the more choices you have about what work to get done and when to do it, the more resilient you will feel.

For example, having a stress and recovery pattern — often a ritual that defines the end of the workday — is essential to feeling resilient, but without a physical separation between home and the workplace, many of us have forsaken our stress-recovery patterns. If you are no longer going into an office to do your work, the natural break of home versus work no longer exists and is replaced instead with one long blur of work-family-home activity.

Although the blurred line between home and work can add layers of stress upon both domains, it can also free us to make our own choices about when to work. That choice is our agency. When we have that choice around our own stress-recovery pattern, we become more resilient. To build more resilience, then, become conscious of which decisions are under your control and determine the choices you can make. For many of us, the pandemic has shattered our rituals of stress and recovery — but this new reality also means that we have more choices about when, where, and how we do our work. We may not be able to share a morning coffee with coworkers or chat with our kid’s teacher at school drop-off, but we can, and we must, create new rituals that fit us during this time. We can walk around our neighborhood during lunchtime each day, start reading The Lord of the Rings out loud every night with our 14-year-old son, or learn to roller-skate at the local park.

Compartmentalization. The next skill you can build to increase your resilience lies with statements 2 and 4: “No matter what else is going on around me, I can stay focused on getting my work done” and “I always believe that things are going to work out for the best.” Those statements reflect how well you are able to compartmentalize.

Compartmentalization is an important cognitive discipline to maintain the sense that things will work out for the best, especially when many things in your life are not going well. The most resilient people seem to realize that life encompasses a number of different lanes, as in a swimming pool. Each swim lane — family, work, physical well-being — is important. Resilient people recognize that although they may be struggling in one swim lane, they’re still coasting along in others. To build resilience, when one thing is going poorly in a single aspect of your life, don’t let it undermine everything else that you have going for you.

Strengths in work. In statement 3, “In the last week, I have felt excited to work every day,” it’s clear that resilience is in part related to your ability to derive strength from your job. Although it may seem counterintuitive, you can actually gain more resilience through work than in spite of it. We each draw strength, love, and joy from very different activities, contexts, and people — one person might get a kick out of closing a sale, while another shies away from asking for the close; one person might love finding patterns in data, while another might be bored by data, lighting up only when it’s time to take action; one person gets a jolt from checking tasks off a list, while another shines only when responding to the emotional state of each teammate. Each of us draws strength from different activities. The most resilient people are able to look at the work that they do and determine which parts of it bring them strength.

Do you know which parts of your job bring you strength? Now would be an excellent time to dig in and learn. When you know which parts of your work strengthen you, pay attention to them. Focus on the activities and situations that bring you joy, because you’re going to need those reservoirs of strengths. Your job in life is to understand and increase the activities that bring you joy in work. You don’t need to fill your day with them — research by the Mayo Clinic suggests that spending merely 20% of your day on activities that you love can have strongly positive effects on your resilience — but you do need to identify which activities you enjoy and cultivate them as a part of your personal resilience ecosystem.1 Stay focused on the activities that strengthen you, and consciously draw their energy into your working life. Getting distracted is the enemy of resilience.

In these times, we could all use a bit (or a lot) more resilience. It is my sincerest hope that this research will help you to understand what causes and impacts it, what your team leader and senior leaders are accountable for, and most important, what you can do to cultivate resilience within yourself.

The Sources of Resilience