Image courtesy of Richard Borge/theispot.com

As the world recovers from the initial shock wave caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, businesses are preparing for their transitions back to their physical workplaces. In most cases, they are opening up gradually, with an unprecedented focus on keeping workers safe as they return. To protect employees’ health and well-being, organizations must systematically reengineer their workspaces. This may include reconfiguring offices, rearranging desks, changing people’s shifts to minimize crowding, and allowing people to work remotely long term. Then there are the purely medical measures, such as regular temperature checks, the provision of face masks and other personal protective equipment, and even onsite doctors. Such precautions would have seemed extreme a short time ago but are quickly becoming accepted practices.

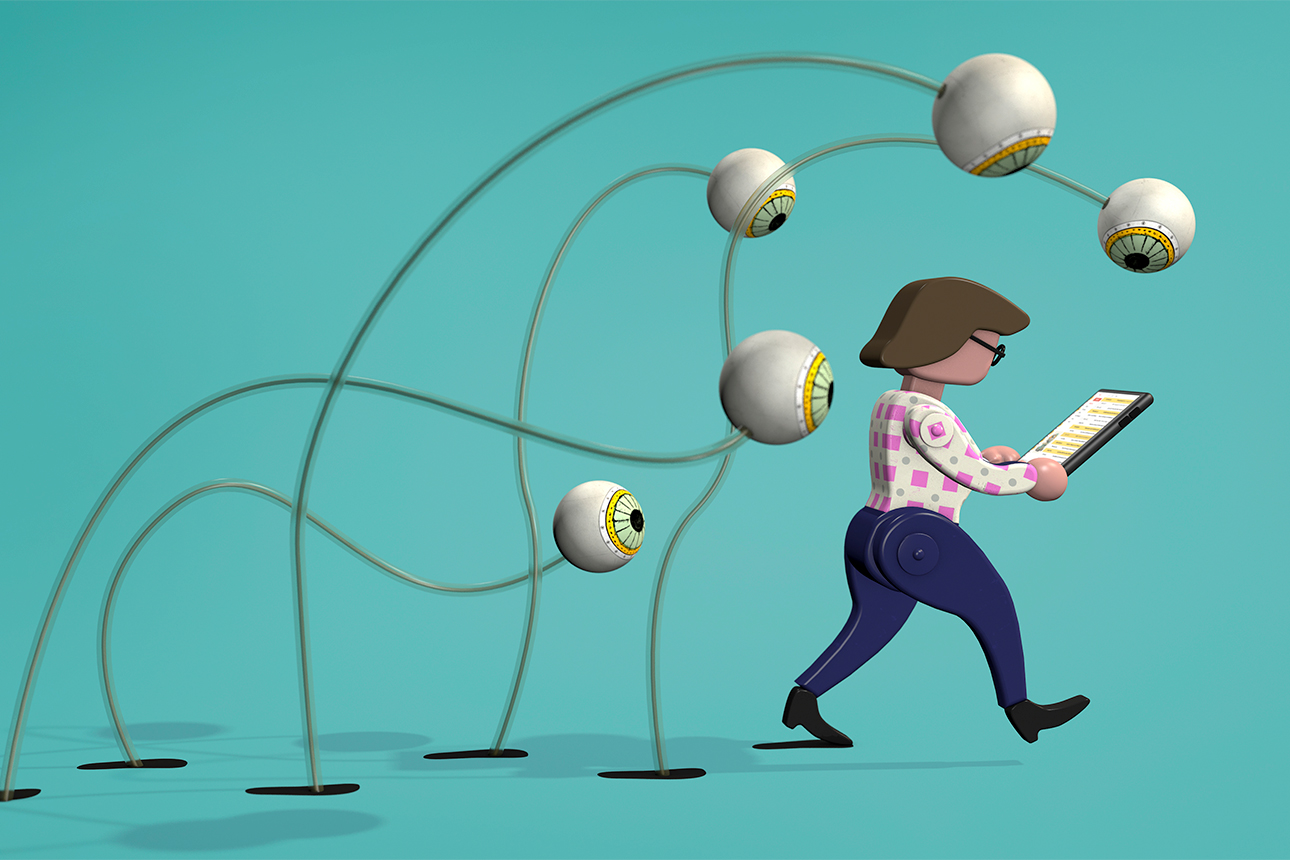

Soon, organizations may also start monitoring employees’ whereabouts and behavior more closely than ever, using surveillance tools such as cellphone apps, office sensors, and algorithms that scrape and analyze the vast amounts of data people produce as they work. Even when they are not in the office, workers generate a sea of data through their interactions on email, Slack, text and instant messaging platforms, videoconferences, and the still-not-extinct phone call. With the help of AI, this data can be translated into automated, real-time diagnostics that gauge people’s health and well-being, their current risk levels, and their likelihood of future risk. A parallel here is the use of various surveillance measures by many governments — with some success — to contain the pandemic (in China, Israel, Singapore, and Australia, for instance). Most notably, track-and-trace tools have been deployed to follow people’s every move, with the intention of isolating infected individuals and reducing contagion.1

Technological surveillance is always controversial, not least for being out of sync with the basic values and tenets underpinning free and democratic societies. Indeed, the idea of using AI to do previously “human” tasks is already quite polarizing; for many of us, the notion of also using it for surveillance adds an element of Orwellian creepiness.

And yet, even in free and democratic societies, we have already given away so much personal data in the digital age that the concept of privacy has been greatly devalued and diluted. Occasionally we did so in the hope of being safer or healthier, but mostly in order to consume more relevant ads, watch more interesting movies, show off from the executive club lounge, and snoop on people we dated in high school (yes, we are apparently capable of being creepy, too).

Moreover, even before the pandemic, businesses were already deploying AI to manage their workforces. Many employers were using it to gauge people’s potential or predict their talents, thanks to the booming field of people analytics.2 In fact, the current rise of data as a dominant currency in HR can be traced back to the beginnings of the scientific management movement over 100 years ago, when Frederick Taylor pioneered efforts to turn large organizations into HR laboratories by measuring employees’ every move to optimize task design and maximize productivity. One could argue that AI has simply furthered that ongoing quest to enhance workforce performance — and that using it to keep employees safe and healthy is another step in that direction.

The Capabilities That Exist

Modeling workers’ health statuses and risk levels and predicting whether people are a threat to their colleagues involves sophisticated work. Most organizations don’t have the tools and capabilities yet, and it’s hard to say how many are making strides, since companies are reluctant to advertise such efforts. But there is a great deal of academic research showing potential for real-world application, including scientific studies identifying various digital signals — the type of data we produce and give away already — as health indicators or risk markers. Some companies have connected these dots in the marketplace: Remember when Target was able to infer that one of its teenage customers was pregnant before her father knew it, by comparing her shopping habits with those of other pregnant customers? And when Google Flu Trends famously predicted population-wide epidemics by aggregating individual searches? To the degree that employers can similarly access behavioral data, they can create health and risk profiles of their workers and intervene to protect their well-being.

Consider, for example, the potential to harness natural language processing, a subfield of computational linguistics that detects connections between individuals’ use of language (which words we use, how often, and in what context) and their emotional, psychological, and health states.3 Because most of our communication — whether via emails, calls, or videoconferences — is now recorded, employers could feasibly deploy AI to identify individual and group-level risk markers. This approach was implemented by universities in Singapore, where videos of onsite classes revealed interactions between sick students and others. With so many meetings happening online, companies could also mine video communications for body language or facial expressions to identify changes in patterns and to assess whether nonverbal expressions, including the physical properties of speech (tone, inflection, pitch, cadence), may signal risk.4

Social network analysis offers additional opportunities for risk assessment and intervention. Email metadata (whom you email, when, and how often) and tracking data from sensors placed in rooms or on people, as pioneered by MIT’s Ben Waber and his company Humanyze, could be used to monitor whether individuals who have exhibited COVID-19 symptoms or tested positive had contact with colleagues, who could then be quarantined. A bit more of a stretch, but not impossible to imagine: Employers might also want to access data from Uber, Waze, Google Maps, WhatsApp, WeChat, or other apps to check where people go, whom they connect with, and what they say. Such data could, in theory, be used not just to diagnose individuals who are not aware of their risks or illness but also to detect those who are keeping secrets.

The Constraints We Need

Before the pandemic, there was already a clear gap between what companies could know and should know about people, and that gap will grow in the near future. People are likely to be less bothered by Google, Facebook, and Amazon scrutinizing their every move — and commercializing their data — than by employers mining their work data. Although the terms of agreements with product and service providers are often buried in fine print, consumers can choose to give or withhold their consent. People don’t necessarily feel empowered to do that as employees, especially if they fear losing their jobs.

To be sure, legal constraints are needed to stop anyone — including employers — from knowing more than they should about us and interfering with our freedoms and rights.5 Still, there are ethical ways to deploy new technologies, including surveillance AI, to promote safety on the job.

First, organizations should ensure that employees know very clearly what the deal is: what data they are collecting and why. Second, once workers are informed about the process and understand the reasons behind it, they should have a chance to opt out without fear of penalty or, even better, proactively choose to opt in because they see the value of doing so. Third, the employees themselves should benefit from sharing their data and having algorithms analyze their activity — whether they are gaining developmental feedback; an increase in job satisfaction or engagement; higher levels of job performance or productivity; or, now, during the pandemic, a sense of protection and a higher probability of staying healthy. By engaging with employees in a transparent way and by sharing high-level findings with them — while preserving individual anonymity and confidentiality — companies can show people that it’s worth opting in and thus attenuate the creepiness of AI.

Of course, managers must know the limitations of the technology, given that false positives and false negatives are so common. This is not a trivial issue. Even in some of the most widely used AI applications, such as Amazon’s recommendations engine, academic estimates suggest that accuracy is around 5%.6 Companies must account for that in their modeling. Furthermore, signals may be predictive but hard to interpret. Most employers lack not only the volume and quality of data that big tech companies have, but also the skilled data scientists to make sense of it. Those organizations would need support from external experts to turn data into automated algorithms that could keep people safe.

Finally, employees must be able to trust their leaders to deploy new technologies, including AI, for good. Earning that trust requires a great deal of transparency — about why and how AI is being used, the key factors driving the system’s recommendations, the technology’s limitations, and the human judgment calls that feed the system and interpret the data. Employees need to feel that their leaders are truly interested in boosting their performance, improving their health, and keeping them safe, and that surveillance AI will make the company a better place to work. Even well-intended efforts to leverage AI to protect people will backfire if companies don’t have a culture of trust and employees are suspicious of those at the top.

Can Surveillance AI Make the Workplace Safe?

No comments:

Post a Comment